"When myth incarnates in the waking world...”

The Magic of Art

by CS Thompson

From the very oldest stories and songs of the human race, to the ongoing appeal and relevance of fantastic art, our species has always felt that there are two realities; the waking world or mundane world and the world of magic, the otherworld of dreams and visions.

Some people have always taken this otherworld as a literal fact; others have always dismissed it and disbelieved in it. Visionaries, mystics and poets have always taken another perspective, as articulated brilliantly by Li Ho, the T'ang Dynasty's ghostly genius: "the gods are here- forever present between somewhere and nowhere."

There is much more than what we see in front of us; there is a magical reality. However, this reality is not bound by the elaborate rules and systems of traditional occultism. The universe of myth and magic cannot be reduced to something that happens in a particular time and place, to something about which we could formulate objective laws and a kind of technology.

This world is as vast as our imagination and vaster than that, as deep as the unconscious and deeper than that. It is accessed primarily within the mind, but it is not defined or limited by the human psyche. It cannot be reduced to archetypes although it generates all archetypes. It cannot be reduced to any anthropological theory although it contains all patterns. It's not that there is some other place or other universe where the magic is literally real in the prosaic sense, a universe that impinges sometimes on our own. That would be a "somewhere." Nor is there no such place, for that would be a "nowhere." It is in this paradox that the magic is found.

Another way of saying this is that the two worlds are a single world. The world of magic is our own world, and the horror and wonder of the mythic realm are simply the waking world in its deeper sense, seen clearly with the eyes of the visionary.

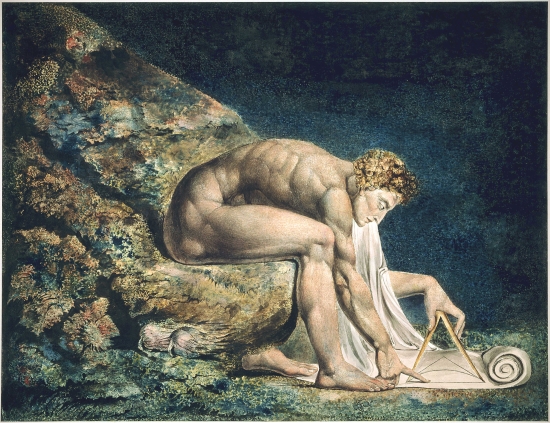

Some artists and writers have always sought to invoke this reality, incarnating it within the waking world. I’m thinking of poets like Li Ho and William Blake, painters like Zdzisław Beksinki.

Li Ho was an unusual figure in the history of Chinese poetry- often referred to as the "ghostly" or "demonic" genius, he devoted himself to the otherworld, painting vivid word-pictures of the Yin realm of Chinese mythology:

Heaven is inscrutable,

Earth keeps its secrets,

The nine-headed monster eats our souls,

Frosts and snows snap our bones.

Dogs are set on us, snarl and sniff around us,

And lick their paws, partial to the orchid-girdled,

Till the end of all afflictions, when God sends us his chariot,

And the sword starred with jewels and the yoke of yellow gold.

I straddle my horse but there is no way back,

On the lake which swamped Li-Yang the waves are huge as mountains,

Deadly dragons stare at me, jostle the rings on the bridle,

Lions and chimaeras spit from slavering mouths.

Pao Chiao slept all his life in the parted fens,

Yen Hui before thirty was flecked at the temples,

Not that Yen Hui had weak blood

Nor that Pao Chiao had offended Heaven:

Heaven dreaded the time when teeth would close and rend them,

For this and this cause only made it so.

Plain though it is, I fear that you still doubt me.

Witness the man who raved at the wall as he wrote his questions

o Heaven.

(Translation by A.C. Graham from "Poems of the Late T’ang)

William Blake was an English poet and painter who created an entire mythology of his own, illustrating it in his Prophetic Books.

Zdzisław Beksiński was a modern Polish artist, who created seemingly photorealistic portrayals of a fantastic world, of crucifixes topped by monstrous spiders and empty, gigantic cathedrals made of blood and flesh.

Three artists with almost nothing in common in terms of cultural heritage or artistic technique, but all of them shared a common mission: the incarnation of another world within the mundane realm.

Wallace Stevens said that poets were the "priests of the invisible," a phrase that could be applied to any art that evokes the mythic realm. The artist of this sort, as a priest of the invisible, travels up in spirit to the land of visions, captures a glimpse of gnosis there and brings it back to incarnate it within an artistic creation. When a painting is viewed or a poem is read, the gnosis encoded within it is invoked and released, taking the viewer or reader on a spiritual journey. To the extent that the reader is receptive to this journey, to its horror and wonder, the person who experiences a piece of art soars upward to the realm of myth to see what the artist saw there.

This is true even of artists who don’t explicitly seek to evoke the mythic the way Li Ho or William Blake did. To everything there is a magic, an essence or inner life, a poetic truth.

The failure to evoke this essence creates a sense of cliche, of tedium and stereotype. To succeed in evoking it is to be original and brilliant, even if what is said has been said before. The reason for this is that the purpose of true art is not originality but insight.

The insight contained within a piece of art encodes the gnosis of that artistic work, the truth that can only be experienced, not intellectually known. A haiku about a frog in a pond contains the gnosis of that experience, as simple and un-mythical as it might appear to be. The feeling of haunting honesty, of almost frightening truth- these things are what art aspires to, even if there is no overtly magical theme.

In this respect, all art is magic.